You’ve seen and heard of the modern performative man: matcha, feminist literature, and tote bags. These curated traits are (supposedly) men’s signals to potential female love interests that they are respectful, progressive, and share similar hobbies.

Let’s discuss what “performative” means and what this trend may reflect about broader society…or, maybe it’s just not that deep? Let me know.

Performative, performative, performative

We can interpret the word “performative” in several ways. First, as James Factora points out in their article for them, “performative” on the Internet usually means “virtue signaling.” It is considered performative, for example, to repost advocacy art on your Instagram story every time something horrific happens without taking meaningful action in real life.

The performative man also shares its name with Judith Butler’s concept of gender performativity from their 1990 book Gender Trouble. As Butler writes,

“Gender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being” (Butler 45).

Gender is not inherent, they argue, but emerges through repeated cultural performances of “man” and “woman.”

Beyond virtue signaling or gender performativity, the performative man is also the most literal version of a performance—it’s a show.

Since the beginning of the trend, the matcha-drinking, Laufey-listening fashionista man existed more in online, hyperbolic and satirical skits than real life. Even when the trend moved offline, it was entertainment through “performative man contests” that required exaggeration and personality.

I would argue that the performative man is a “show” and “virtue signaling,” but it is not an investigation into gender expression, even if it may offer a chance to play with it. However, this overlap of language has pushed many journalists and Internet users alike to grapple with Butler’s dense text and what it means to perform gender, and the performative man offers a clear example of what it looks like to intentionally and aesthetically present your gender.

Where did he come from?

Amplifying historically desirable traits of masculinity in order to attract women isn’t new: what once may have been flashy wealth and brute strength is now feminist enlightenment and good style. So, what’s so enticing and troublesome for people about this particular iteration of a mating call?

I first remember seeing videos of NYC men “reading” in public in 2024 – it was a video of a generic white man reading Emily Ratajkowski’s My Body in the West Village. Whether it began as a skit or someone had genuinely filmed a man reading in public, it doesn’t matter; the exaggerated and taunting videos started snowballing, all the way to the trend’s peak in 2025. Examples below:

I’m more interested in why this trend became a thing, and why now. Why do men feel they must signal their politics to get a girl? Why do we immediately mock and parody that man and assume insincerity?

I think the performative man trend represents a conflicted moment for masculinity, which is caught between a need to evolve and a society that scrutinizes every attempt to redefine it. It’s both a push-back against progressing gender norms and a way to experiment with them safely and at an ironic distance.

The push-back

On the one hand, we can view the performative man as a reaction to fragmenting masculinities and diverging politics between genders. The performative man becomes a very tangible target for those worrying about the changing gender landscape. Men (and women!) can self-police masculinity under the guise of comedy, entertainment, and protecting women from harm and deception (similar to the rationale for keeping trans women out of the women’s bathroom).

There are way more men concerned about others altering their personal aesthetics to lure women with a curated facade of wokeness than there are men actually doing that, which demonstrates where society’s real fears lie.

Young women are becoming more liberal and young men are becoming more conservative. It makes sense that the trend involves a “fake” adoption of liberal aesthetics and values to attract women back.

We can also see the ideological split amongst men play out in the performative man. The red-pill, “man-o-sphere,” conservative men can suddenly no longer woo liberal women with traditional gender roles, so they discredit more progressive men as deceptive while affirming their own legitimacy. The trend targets inauthenticity (the Internet’s new favorite enemy) instead of queerness, and allows macho men to mock the less masculine without appearing overtly homophobic.

The memeification of the performative man also helps to dismiss any man who has an actual interest in feminist literature or female singer-songwriters. By being so easily packaged in a “performative man starter pack,” this persona is revealed as easily replicable and therefore even more inauthentic if someone adopts it. Any man seeking to meet women at their level is now just a meme, reduced to a self-serving copycat.

While these macho men are not the ones necessarily participating in the TikTok trends and real-life competitions, dominant cultural trends often serve the interests of the patriarchy. Even if, on the surface level, we see a character that values feminism and respects women’s interests, the trend’s rhetoric is about making fun of him.

An ironic experimentation

On the other hand, the performative man is a way for men to dip their toes into softer expressions while maintaining plausible deniability. As they redesign their personal aesthetics, they do so through an ironic and safe distance and never have to fully own the more feminine version of masculinity. It becomes an easily backtrackable “bit” in which they are just poking fun.

Donning this “costume” may be liberating to men who wish to safely push the boundaries of male expression. It can also be comforting to have an easily identifiable aesthetic that fits within the social hierarchy, and perhaps it’s a baby step towards a more transgressive life.

However, because it’s rooted in mockery and hyperbole, it does nothing to make the world more accepting of alternative masculinities.

And it’s not just the people making fun of the performative man. It’s the performative men themselves, refusing to fully take on the risk of challenging traditional masculinity.

In 2012, Christy Wampole published “How to Live Without Irony” in the New York Times to analyze the hipster who uses irony as a self-aware shield against criticism. “Irony,” she writes, “is the most self-defensive mode, as it allows a person to dodge responsibility for his or her choices, aesthetic and otherwise. To live ironically is to hide in public.”

She says that irony “signals a deep aversion to risk.” The performative man, I’d argue, avoids the risk of non-traditional masculinity, self improvement, and caring about relationships with women.

“If life has become merely a clutter of kitsch objects, an endless series of sarcastic jokes and pop references, a competition to see who can care the least (or, at minimum, a performance of such a competition), it seems we’ve made a collective misstep. Could this be the cause of our emptiness and existential malaise? Or a symptom?”

With Labubus, Laufey, and a literal competition for who can be the most ironic, the performative man is an epitome of the ironic lifestyle that Wampole discusses. It’s both a competition of performance and a performance of competition. The in-person spectacle offers safety in numbers, and it’s a performance of a performance that even further distances the participants from the subject matter.

Instead of hyperbolizing and memeifying a man that challenges traditional masculinity, what if we explored what it would be like to embrace those traits without irony? And on the flip side, instead of signaling one’s values through style and music choices, what if we actually commit to the fundamental betterment of the self and community (i.e. actually read that feminist theory)?

Wampole asks: “How would it feel to change yourself quietly offline, without public display, from within?”

The performative man trend allowed many young men to safely try on new aesthetics and masculinities. As it dies down and becomes oversaturated, I’m curious to see who continues to engage with it and how the trend reinvents itself. I hope that it has taken us one step closer to a mass realization of the mutability of gender, now that the words “performative” and “gender” have entered mainstream vocabularies together.

We don’t have to announce who we want to be…we can just be. In the age of AI art and entertainment that lacks human feeling, our vulnerability, desire, and sincerity are the most valuable things we have.

P.S. — Some related moments/ideas I’m thinking about:

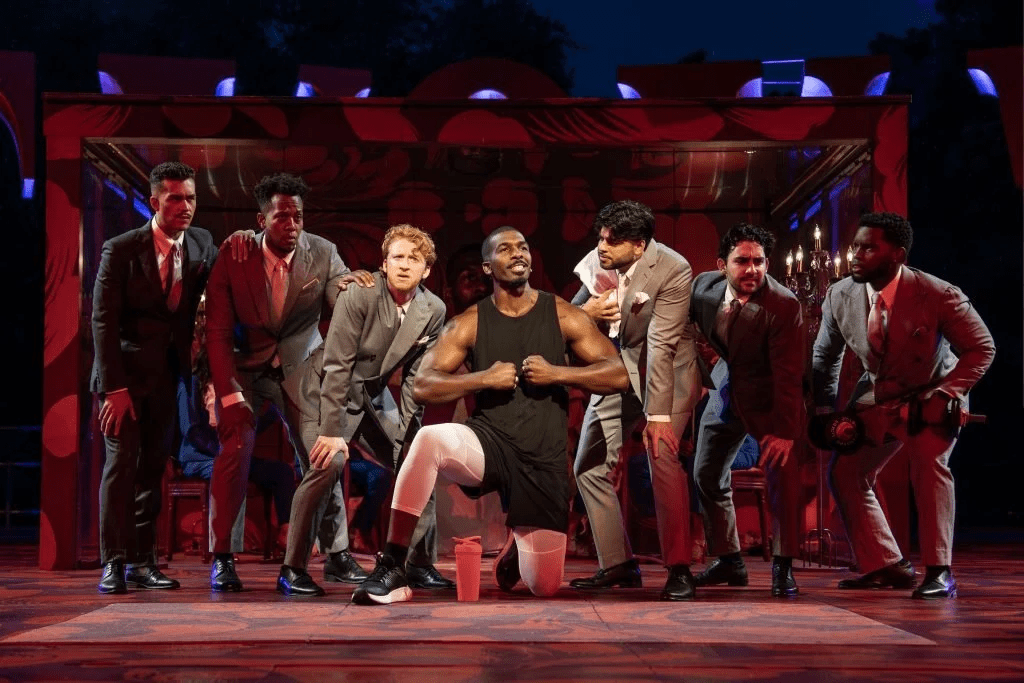

The Public’s Shakespeare in the Park production of Twelfth Night that I saw this summer, with its gender-bending love triangle and gender performance. It represented Orsino as a stereotypical iron-pumping douchebag and began the performance with the Fool singing a line from As You Like It: “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.”

A Tumblr post by singer Ethel Cain, where she writes that “we are in an irony epidemic.” Cain’s music deals with complicated and difficult themes like cannibalism and sexual violence, yet the Internet constantly turns them into a joke. Her art is art that affects, but fans deflect with humor, unable to internalize and be affected by raw, and often uncomfortable, emotion. She expresses her frustration in this now-deleted post.

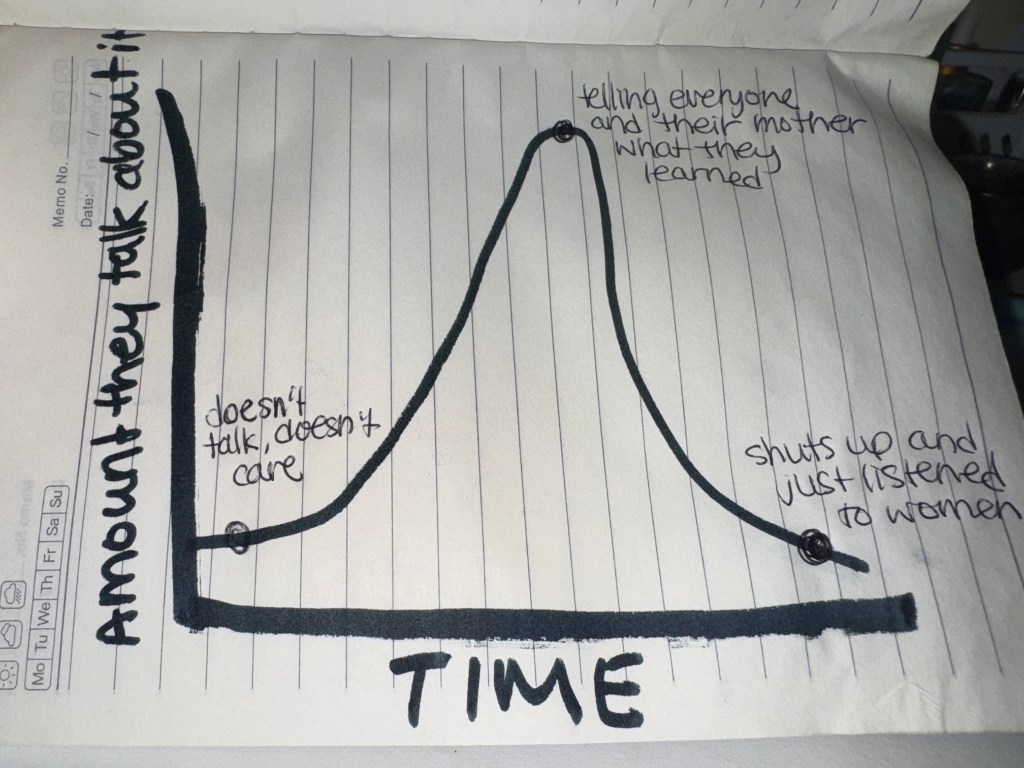

This graph I made to depict men’s feminist journeys: Theoretically, a trend popularizing men reading feminist literature sounds great, but not when the point of the trend is literally to “fake” read it for a man’s own benefit… that’s not very feminist! It enforces a post-feminism culture and gives men no incentive to actually stride towards progress as they’d be equally as made fun of if they actually read the books!

Below is how I envision a man’s journey with feminist theory in my mind. A man first discovers some aspect of feminism and wants to tell everyone what he’s learned. He may even broadcast the fact that he’s reading it to imply he’s “better” than other men.

Then, the more he reads, he realizes the importance of learning quietly, applying what he can to his own life, and listening to women without drawing the attention back to himself.

My graph: A man reading feminist theory’s journey:

Thank you for reading!! xoxo

Leave a comment